Introduction to Croquet

|

There are 2 forms of Croquet: Golf Croquet and Association Croquet and you can read about them here. You can also learn about the history of Croquet in Scotland and about how it has featured in the popular imagination. By Fergus McInnes. Reproduced from the SCA Handbook by kind permission of the author and the SCA. Golf Croquet can be played by up to four players. If only two are playing, one takes red and yellow and the other blue and black. Four players would take one ball each and would play in partnership, again red and yellow against blue and black. Play is in strict rotation — blue, red, black, yellow; the order is shown on the centre peg. (The alternate coloured balls play in the order green, pink, brown, white.) Each turn consists of one stroke only. At the start of the game, a coin is tossed, and the winner can choose which pair of colours to take. Blue (or green) always plays first. You start from anywhere within one yard of corner four (you can measure it with your mallet) and play first towards hoop 1. The first person to run the hoop scores the point and ALL move on to hoop 2, playing their balls from where they lie (with an important exception — see "penalty spots" below). And so on. Normally you play until one side has scored seven points. If the scores are level after 12 hoops you then play hoop 3 again as the 13th and last hoop. You do not have to run a hoop completely in one turn to score it. If your ball starts to run the hoop but sticks part way through, it is up to your opponent to try to knock it back out before you make it finish running the hoop. (A ball starts to run a hoop when it protrudes beyond the non-playing side of the hoop, and completes running the hoop when it cannot be touched by a straight edge placed against the uprights on the playing side.) You may play towards the next hoop if you think another ball (even your partner ball) is certain to score this hoop, but only as far as "halfway" — that is an imaginary line across your path, parallel to a lawn boundary and halfway towards your next hoop. If a ball goes off the court it is replaced on the boundary at the point where it went off— not on a "yard line". Penalty spots If a ball is played towards the next hoop and goes beyond the halfway line, once the current hoop is scored that ball comes back to a "penalty spot". There are two penalty spots — one on each of the East and West boundaries half way along — opposite the peg. The opponent of the player of the penalised ball chooses which spot he wants to put his ball on. However, if the ball has struck an opponent's ball on the way, it is not penalised and is allowed to stay where it is. Tips on tactics You are allowed to cause your ball to jump (normally by hitting down on it so that it leaps up in the air) over another ball to run your hoop. You may hamper your opponent by playing into the hoop (possibly from behind) so that he will have more difficulty in going through. Or you can play your ball so close behind his that he cannot hit his ball cleanly in the desired direction without touching yours (which would be a fault). You can nudge your partner ball into position to run the hoop; or if your partner ball has stuck in the jaws of the hoop you can use your ball to knock it right through, thereby scoring the point. You can use your ball (say red) to drive away an opponent (black) who is in position to run the hoop, or who is in a position where he could knock away your partner (yellow) who is in position to run the hoop.

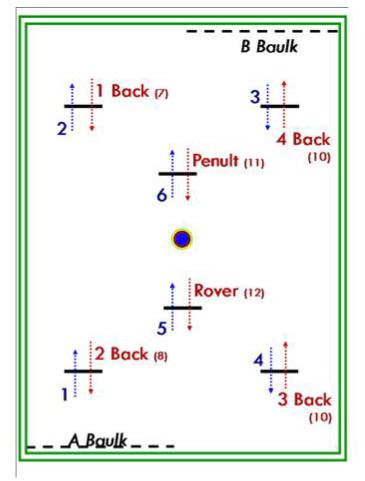

Association Croquet: An Introduction for Innocent Bystanders By Rod Williams. Reproduced from the SCA Handbook by kind permission of the author and the SCA. Snooker on grass? The modern game of Association Croquet has many similarities to snooker, and indeed has sometimes been referred to as snooker on grass. The most obvious thing it shares with snooker is the idea of striking a ball so that it hits another ball to make it to go to a particular place. But it also shares some of the less obvious things, like the concepts of a break, in which more than one point is scored in a turn, and safety shots, in which a player will simply try to make things difficult for the opponent rather than try something difficult himself. One of the hardest things for an aspiring snooker player is to compile a break of more than a few points; the better the player, the larger the break he will be able to put together. Croquet is different; although compiling a decent-sized break is not easy, a good club player will be able to score a significant break if the balls are well set up. The player’s difficulty is getting the balls set up into a good position in the first place; the better the player, the more likely he is to set up the balls for a break from a difficult position. It's worth noting here that, although the largest break under normal circumstances is 12 (one ball through its course of 12 hoops — see the diagram), this is likely to need 80 or more strokes to do. But first let's get a few basic ideas together. The object of Association Croquet The object of croquet is to put your balls through the hoops in a particular order and then hit the centre peg with them before your opponent does so with his balls (see diagram). The winner scores 26 points (one for each ball through its course of 12 hoops and one for hitting it onto the centre peg). The loser scores anything from 0 to 25. One player has the red and yellow balls and the other the blue and black. The players take turns to play, as in snooker, with the "out player" sitting on the sidelines waiting for the opponent to finish either by making a mistake or by playing a safety shot. At the start of a turn a player may play whichever of his two balls he likes. A turn consists basically of one shot, but just as in snooker, a player can earn extra shots. In snooker there is only one way to do this (by potting a ball of the right colour) but in croquet there are two quite different ways of earning extra strokes: by hitting your ball through its hoop or by making your ball hit one of the others — a "roquet" (more about roquets later). Running the correct hoop entitles the player to one extra stroke and also scores a point: making a roquet earns two extra strokes but no points. There isn't much margin for error in running a hoop: the space between the uprights is only Vs" more than the diameter of the ball. So you have to be pretty close to a hoop before you can be sure of running it. How do you get in front of a hoop? This is where the "roquet" and "croquet" shots come in. Roquets and Croquets A "roquet" is made when a player makes his ball hit one of the others; he earns two extra strokes by making a roquet: a "croquet" stroke and a "continuation" stroke. When he has made a roquet the player picks up the ball he is playing (let's say it is red) and puts it down again in contact with the ball he has roqueted (for example blue) wherever it has come to rest. He follows this with a "croquet" stroke in which he again hits red with his mallet, moving both it and blue. In a roquet, it doesn't much matter where the player's ball (red) goes after it hits the other ball, since it is going to be picked up and placed in contact with the other ball (blue). But in the croquet stroke it does matter, because the next stroke is going to be played from where it finishes up. A good player will often try to roquet a ball to a particular spot on the lawn if he can, so that he is taking croquet from the best place. A croquet stroke must be played with the two balls in contact and both balls must be made to move. A good player will also use the croquet stroke to try and put both the balls to particular spots on the lawn. For instance, he might try to put the ball he is striking (red) straight in front of its hoop so that he can run it in the next stroke, or he might try to put it close to another ball so that he will be able to make another roquet. He might try to put the croqueted ball (blue) somewhere where it will come in useful later if his break-building plans work out (see below). He then takes one further shot, called a "continuation" stroke. If in the continuation stroke the player manages to make red run its hoop he scores a point and earns an extra stroke. If he is not in a position to do that, he may roquet another ball (yellow or black in this example) and take croquet from it. He would then follow this with another continuation shot, which itself may be a hoop-running attempt or yet another roquet. However, a player cannot go on like this roqueting ball after ball forever, because he is not allowed to roquet the same ball again until either he has run his hoop or his opponent has had a turn, which will happen if he misses a ball or fails to get his hoop. Break Play Good players are capable of making breaks in which they run several hoops, or even all 12 of them for one ball, in one turn. They do this by using both roquet and croquet strokes to place the other balls (not just their own) in the best strategic positions. That is, in places on the lawn that will make later shots in that turn much easier. It is possible to play a break using only your own two balls (red roquets yellow, takes croquet to land red in front of its hoop, runs hoop, roquets yellow again, croquets to land in front of red's next hoop, runs it, roquets yellow, etc.). This requires an enormous amount of skill, however, and usually quite a lot of luck as well, and it is soon likely to result in failure (missing a roquet or failing a hoop). This may let the opponent in to score. It is much easier to play a high-scoring break if all four balls are being used (how it's done is left as an exercise to the reader!) but this has to be balanced against the risk that if it fails it gives the opponent a much easier chance of a high-scoring break for himself. A good player will usually go out of his way to bring the opponent's balls into the break, because the benefits of having all four balls in the break will usually outweigh the risks. Strategy Because of this balancing of risks, a game of croquet may have periods of purely defensive manoeuvring involving only a few strokes, by both sides, while each is trying to gain some positional advantage before risking an attack to try to set up a break which brings the opponent's balls into play. The attacker has to balance the likelihood of his success in first setting up, and then completing, a break, against the possibility of leaving the opponent an "easy" break if he fails. Also, if he doesn't attack first, the opponent may do so and score a break himself. Or the opponent may fail in his own attempt to set up a break.... One of the players will eventually decide to attack and, if successful, will compile a useful lead. If not, however, he will usually have given his opponent a good position for him to score several points. The Finish The game finishes when a player hits both his balls on to the centre peg after running all the hoops with both balls. In snooker, once one player has a big enough lead the game is virtually over and further play is pointless. In croquet a game is never over until the final peg-out; many a game has been lost because a player failed to hit the peg in his final stroke, while the opponent had yet to score. In theory, the game is usually finished by: 1. Taking one ball through its last hoop or hoops (probably while making a break) and "laying up" for the other ball to score its remaining hoops. That is, you leave yourself easy break chances for the second ball, but make sure your opponent only has difficult long shots. 2. The opponent then, you hope, misses the difficult shot you have left for him (you must leave him a shot; you can't hide all the balls behind hoops). 3. You then play a break for your second ball (using all the other balls to make your break easier if possible) through all its remaining hoops, finally roqueting your other ball close to the peg, croqueting it onto the peg (and out of the game) and finally, with your remaining continuation stroke, hit your ball onto the peg to score your 26th point and win the game. In reality life is not usually so kind, and part of the fascination of croquet is working out how to recover from a mess you have got yourself into by playing a poor stroke (maybe you only just ran through the hoop, not giving yourself a chance of the shot you hoped would follow), or the mess your opponent has put you in (maybe by leaving your two balls "snookered" by a hoop). Choices always have to be made: "If I miss this shot, what will my opponent be able to do with it? Will he score a big break? Should I take a different shot?" or "Should I play a safety shot and try to set things up again a few turns later?" And there is very often the "Oh, dear! I didn't think he would do that!" or even more exasperating, "Damn! Why didn't I think of that?" Variations on a Theme There are several different versions of association croquet: In Doubles each player of a side plays just one of the balls: the opponents' strategy is generally to force the weaker player to take the difficult turns. In Handicap games the weaker player takes a certain number of free turns, based on the difference between the players' handicaps. These free turns can be taken at any time when he would normally leave the lawn to let the opponent on. They can be used to recover from disasters like a missed roquet or a missed hoop or they can be used more tactically in setting up a break from a difficult position. The handicap system in croquet works very well. Another variant of the game is Short Croquet. The major differences between Association Croquet and Short Croquet are: 1. It is played on a half-size lawn. This makes the positional strokes much easier. 2. Only the first circuit of six hoops is completed by each ball before the peg point is scored. This means the total number of points scored by the winner is 14 (6 hoops for each of his two balls plus 2 peg points). This makes the game much shorter. Golf Croquet is altogether a much simpler game, in which there is no such thing as a croquet stroke or a continuation stroke. Tactics in this game involve blocking the way to the hoop and knocking the opponent's balls out of the way. Also, unlike Association Croquet the balls are played in the same order all the time.

The Early days of Croquet in Scotland By Ian H. Wright. Reproduced from the SCA Handbook by kind permission of the author and the SCA. The early days of croquet in The earliest known reference to croquet in Throwing stately homes open to the public, and organising money making events in the grounds is not just something invented by the aristocracy as a means of keeping their estates intact since the Second World War. They were at it in the nineteenth century too. Jousting events were apparently held regularly at The next known date, 1869, was established by one of the exciting finds referred to above. A mallet bearing this date was recently discovered in the club room of the Edinburgh Croquet Club. The name "Highgate" was also painted on the mallet head and the final thing to clinch its origin was the barely decipherable name and address of the retailer "Buchanan 215 Piccadilly", on the under-side of the head. Research showed that this was almost certain to have been a quarter-finalist's prize at a championship held at Highgate that year, and that the famous David MacFie who lived in The importance of this find, however, is that it shows that as early as 1869 there was in Two years later, 1871, is the early date best known among croquet players in Scotland because it is the date inscribed on the side of our most famous trophy — the Moffat Mallet. This bears the original inscription "Champion of Scotland" and is held each year by the Open Singles Champion. This mallet, again found in Further light was shed on this period as recently as 1990 when the other exciting find referred to above happened. A magnificent solid gold medal was found in an old box in Gleneagles Hotel. It was inscribed "Scottish Croquet Club Championship of Scotland For Annual Competition". On the back of the medal were the names of all holders from 1875 to 1906, while on two gold bars attached to the blue, red, black and yellow ribbon were further winners up to 1914. This important find has filled in several blanks in the knowledge of croquet in the last century. The words "Scottish Croquet Club" show that the game was organised nationally, and that there has been a forerunner to the Scottish Croquet Association. An article in the Moffat News of The other interesting fact confirmed by the medal is that croquet in However, eventually sense prevailed and in the late 1890's there was a revival of the Queen of Lawn Games, and with it, the Scottish Championship. However, the venue was no longer Moffat. From 1897 to the last date on the medal, 1914, it was held in At that same venue, between 1908 and 1914, competitions were held for Scottish

Gold Medals which were presented by the Croquet Association. These were separate events for men and women. Was the CA the "governing body" responsible for croquet in

Before the SCA From the onset of the First World War right until the founding of the Edinburgh Croquet Club in 1950 the history of croquet in Throughout this period golf croquet was played fairly widely in In those days women were not allowed to play bowls and so in 1913 they sought to use a spare area of the bowling club grounds to set up a small croquet court for the ladies to play on. It took until 1921 before their plans bore fruit (was it a coincidence that women had just got the vote?). So far as is known Livilands was the only club playing the association game until Edinburgh Croquet Club started in 1950, although they played with two pegs right until the end. This came in 1976 when expansion at the Stirling Infirmary meant that the ground was needed for a nurses' residence. A similar area of ground was given to the bowling club somewhere else in exchange but, instead of a small croquet court, a car park was laid. In 1949 the Monquhitter Croquet Club in Aberdeenshire was the first club to start up after the Second World War. It was another ladies' club, also associated with a bowling club, and which played only golf croquet. One or two other smaller golf croquet clubs started up in that area, too, in the villages of New Deer, Maud and Ellen. There was a good spirit of competition between them, and the Aberdeen Press & Journal frequently carried reports of their matches and events. The first club to start that played Association Croquet was in The next club to start in By September 1959 a suitable ground had been found in Pollok Estate, and a meeting of prospective members was held in that month. By early April the next year, even before the two courts were ready for play, the new club already had 42 members and a waiting list had been started. One of the two courts was level but the other was far from being so. It was in a field running down to the river and had a drop of over six feet from end to end. Despite this the club thrived. The social side was always strong in the Modem Association Croquet was brought to the In the same year another club was started in the Glasgow Area, at Also in 1967 Jack Norton started a third club — one with a difference. It was the croquet section of the Incorrigibles Club. This was a club that, like the other sections, had no home ground. Membership was by invitation only, and they would travel anywhere for a match — one was even played in In 1969 The Whins Croquet Club was started at the National Coal Board Area Headquarters in Alloa by lan Wright. This was also mainly a lunchtime club. In 1973 the office in Alloa closed, and after trying several other locations unsuccessfully the club folded. Another club in the The game has also been played at 1967 was the Centenary of the Croquet Association and this was to be marked by a nationwide tournament called the "All-England Handicap". Naturally the Edinburgh Club wrote to complain that this name was "not fully representative of those entering it". They received the interesting reply that the name had been chosen because the Croquet Association already had a stock of bronze medals (for the eleven Area winners) with that name engraved on them! Anyway, All-England or not Ronnie Sinclair of the Edinburgh Club won the National Final at the Hurlingham Club, and was presented with a commemorative rose bowl by Her Majesty the Queen. At the Scottish Area Final that year Ronnie Sinclair had also been Presented with the “Moffat Mallet", recently acquired by the Edinburgh Club, and now the annual trophy for the Scottish Open Singles. This was the first of a succession of All-England handicap wins in the following three years by players from Following the success in the All-England Handicap the Edinburgh Club set its sights on a Scottish Open Championship for the following season. This and other matters were discussed at an informal meeting after the Glasgow Club's Annual Dinner in March 1968, and thus the Scottish Croquet Committee was born. Aided by the Croquet Association this committee was formalised the following spring with members from the Edinburgh, Glasgow, Glenochil, Langside and Philipshill clubs. The new Open Championship was open to anyone in The next year also saw another milestone in Scottish croquet when the first Edinburgh Tournament was held. Finding a flat area of reasonable grass big enough for several croquet courts is not easy but permission was obtained to use one of the hockey pitches at the Dunfermline College of Physical Education in Cramond about a mile from With assistance from the Croquet Association, who provided the manager Derek Caporn, this first week-long tournament was a success. However it was decided not to hold one m 1970 because the playing surface was so poor, and it was felt that this would deter any players from By this time the next series of Test Matches for the MacRobertson Shield to be held in In the event the The money was raised, and the match was played, and it proved a turning point for Scottish croquet. It was played to the same format as the Test matches — teams of six playing three doubles and six singles, each best of three games. The boost to the morale of Scottish players was tremendous, and this led to Scottish players entering tournaments in Very early in the seventies the Glasgow Croquet Club was finding that its single flat court and two very sloping ones were not good enough, and was looking for somewhere better. A nearby area was found which could be purchased cheaply, and Scottish Sports Council aid was sought. This raised the problem that the Council could deal only with properly constituted, fully autonomous governing bodies and croquet in Steps were then put in train to form the Scottish Croquet Association. Again the Croquet Association were very helpful in this and a sub-committee chaired by Robert Milne of the Edinburgh Club, set about devising a constitution. In due course, after much discussion and many changes, a constitution was agreed. Then in May 1974 an Inaugural Meeting was held in the At last, in May 1974,

Croquet in the Popular Imagination By John M. Clark Most people, on those rare occasions when they think of croquet, conjure up images of impossibly stiff Victorian men and women indulging in a genteel pastime in impeccable gardens. As usual, the reality is a little different. It is generally accepted that croquet was introduced to Britain from Ireland in the 1850s and from there spread like wildfire across the Empire and America, becoming enormously popular with the upper and middle classes, in part for one very good reason: sex. When a young lady hit her ball into the rhododendron bushes it was incumbent upon a young gentleman to help her find it, which is how couples got away from their chaperone for ten minutes.

Croquet’s popularity also owed something to Victorian sexism. It was one of a number of games and pastimes emerging at this time, including archery, cycling and, later, tennis, that were considered suitable for women, in part because in their original form they did not involve anything so vulgar as scoring or competition (remember that the original object of tennis was to keep a rally going for as long as possible, rather than to try to score points). This attitude was particularly prevalent in By this time though rules of public behaviour were becoming more relaxed and young women were now allowed to run around and get hot and sweaty in public. Consequently croquet gradually gave way to tennis; a tennis court is half the size of a croquet lawn for this very reason.

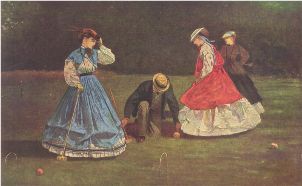

However, the game had already made its mark in both high and popular culture. Croquet’s period of greatest popularity coincided with one of the great artistic movements of the nineteenth century: Impressionism. The Impressionists overturned many of the prevailing conventions, most notably in their preference for painting en plein air and choosing everyday life as their subject matter rather than lofty classical or biblical scenes. Croquet was thus a natural for the Impressionists and their contemporaries. Perhaps the best known croquet painting is Édouard Manet’s The Croquet Game (1874) which shows four bourgeois playing a game in what appears to be a fairly rustic setting. The same title is given to works by, amongst others, Louise Abbema, Pierre Bonnard and the American Winslow Homer, who painted several croquet scenes. (These and other paintings and illustrations can be seen on the website of Hawaii's Maui Croquet Club.) Croquet also featured prominently in popular literature. Jo March and her sisters spend an afternoon playing croquet at a neighbour’s summer picnic in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868), whereby they learn valuable lessons about fair play and national pride (I kid you not, see below). Anthony Trollope used a quarrel over the rules of croquet as a metaphor for the larger struggle between the principle characters in The Small House at Allington (1862), while H.G. Wells used the game in The Croquet Player (1937) as a metaphor for the way man confronts the very problem of his existence (or so it says on Wikipedia, so it’s probably false... sorry, true. Only kidding.)

But the best known example today is, of course, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The image of Which is all very well, but rather reinforces the idea of croquet as an ancient pastime. What of other, more up-to-date examples? Well, it’s still all about status and rules, although these days people also like to subvert croquet's genteel image. Take the film Heathers, the 1989 schlock-fest starring Christian Slater and Winona Ryder. The titular trio of queen bees are seen playing croquet to establish how terribly upper-crust they are, but also as a means of showing us how cruel and ruthless they are, even, perhaps especially, amongst themselves. Who can forget that magnificent scene where the Heathers put Veronica to the test by burying her up to her neck then using her head for target practice? Here the rules are those of the Then there’s Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson’s touching and hilarious comic-strip about a small boy and his toy tiger. Here again it’s all about rules; “Our favourite games are the ones we don’t understand” is a quote from one of the earliest croquet-featuring strips. Evolving over time into the gloriously inspired anarchy of Calvinball, croquet was one of the recurring vehicles over the ten years of the strip’s life for exploring both Calvin’s struggle to comprehend the rules of normal life and his casual propensity to innocent violence (“The temptation to mis-use these things [croquet mallets] is immense” is another classic quote).

Mention must be made of Kate Atkinson’s second novel Human Croquet, which has absolutely nothing to do with croquet, but is a wonderful novel nonetheless.

However, when it comes to croquet in modern literature there is really no-one who can compare with Jasper Fforde. His Thursday Next novels are set in a parallel world where dodos, mammoths and Neanderthals are still with us, where literature still matters and croquet is the most popular sport in the country. Something Rotten, the fourth Thursday Next novel, describes how Ms. Next, a literary detective by trade, found herself playing for the Swindon Mallets in front of over 30,000 fans in the 1988 Superhoop final against Reading Whackers, desperately trying to win the game and save the world in the process. (I’ll leave it to you to decide which is more important… croquet match… world… tough decision. As for how winning a croquet match could save the world... well, you'll just have to read the books.) “Nextian” croquet is superficially rather unlike “real” croquet, in that it is a team sport involving extreme violence and pain, and yet at the same time is, in certain crucial aspects, almost exactly like real croquet, viz. “I had touched the opponent’s ball when south of the forty-yard line after it had been passed from the last person to have hit a red ball in the opposite direction – one of the more obvious offside transgressions”. I think it is fair to say that whilst Japser may not have the greatest grasp of the actual laws of the game (I know, I’ve asked him – just had to get in that I’ve met him!) he certainly understands the spirit of the laws. (Non-players should not let this put them off trying the game - it's not that the laws are really that complex it's just that they sometimes seem that complex.) But at bottom, croquet remains, in the popular imagination, a game for toffs. Think of the fuss when it emerged in May 2006 that John Prescott, popular champion of the “prolier-than-thou” tendency of the Labour Party, had a secret love of the game. If he’d been caught biting the heads off live chickens it would have caused less of a sensation* than his “croquet-playing antics” . But that’s only the prejudices of the redtops. You don’t think like that, do you…? * From a Telegraph leader: “We do not begrudge Mr Prescott his free time, nor his surprisingly middle-class choice of game. Labour activists may moan at the embourgeoisement of the last proletarian minister, but this newspaper deprecates such snobbery.” Pass the sick bag please.

|